Read our Monthly Magazine

And support our mission to provide fearless stories about and outside the media system

The leaked reports suggesting that the UK has suspended intelligence cooperation with the US over its lethal strikes against boats allegedly smuggling drugs through the Caribbean risks wider ramifications for UK-US intelligence cooperation, but only if the US chooses to overreact.

The UK’s decision does not reflect any move to go “soft” on drugs, as some in the Trump administration might try to allege. Nor does it mean that the UK sympathizes with the Maduro regime in Venezuela, which many analysts believe is the true target of the US’s more assertive posture in the region, part of a wider strategy to increase pressure on the regime and stimulate an internal coup against Maduro.

The UK has consistently stood with the US and other international partners in condemning Maduro’s authoritarian rule in Venezuela, and denouncing his claim to the Presidency as illegitimate following contested elections last summer. Earlier this year, the UK imposed sanctions on 15 individuals closely associated with his regime.

The UK’s decision seems to have been motivated purely by a concern that it not be directly implicated in the US’s attacks, which numerous international experts, including the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, have said is a form of extrajudicial killing, illegal under international law. There have been 19 attacks on boats so far, resulting in the deaths of at least 76 people. They have apparently taken place without any warnings to the people onboard, or with irrefutable proof that the boats were indeed carrying drugs, and destined for the US mainland.

The UK could face legal jeopardy, because it has traditionally cooperated closely with US organisations combatting drug trafficking in the region, including by sharing intelligence, and stationing a liaison officer at the main centre for tracking drug movements and conducting counter-narcotic operations in the Caribbean, the Joint Interagency Task Force South unit in Key West, Florida.

The UK also has a naval officer onboard one of the US warships, the USS Winston Churchill, which is part of a larger naval strike force, including an aircraft carrier, which the US is moving into the region. This officer could potentially become personally liable, if he is on board a ship which takes part in illegal operations.

Earlier this year, the Trump administration tried to establish legal cover for its attacks by designating drug traffickers as “enemy combatants” engaged in an armed conflict against the US, and certain drug cartels as “foreign terrorist groups”. While it is certainly true that drug-related deaths have soared in the US, and that drug gangs in Latin America are notoriously violent, their main destabilizing effects are felt in drug producing countries, such as Colombia, or transit countries, such as Mexico. There can be no credible claim that drug gangs pose such a serious security threat to the US, that it would justify a full-on military response

Moreover, the most serious drug problems in the US today are caused by synthetic drugs such as fentanyl, which are trafficked mainly through Mexico, and produced using chemicals sourced from China. According to Michael Shifter, former President of the Inter-American Dialogue, a leading Latin America think tank in Washington, whom I spoke to a few weeks ago about what might be behind US actions in the Caribbean, Venezuela, while certainly home to many criminal drug groups, is largely irrelevant to the fentanyl issue.

Shifter’s believes that the US administration’s decision to portray its military posture in the region as part of a strategy to combat “narco-terrorism” is because that is more likely to appeal to MAGA supporters, who in part backed Trump because he promised to end “forever wars” linked to regime change. Trump himself probably does not care one whit about Maduro’s record on democracy, and has shown himself perfectly willing to deal with authoritarian regimes in other parts of the world. Trump might see the boat attacks as an easy way to deflect attention from his domestic problems, by playing to his image as a “tough guy” not afraid to take on the “bad guys.”

Shifter believes the person really driving the strategy is Secretary of State and National Security advisor, Marco Rubio, who does have a long record of opposition to the Maduro regime, and its backers in Cuba. He is sceptical that Rubio’s scheme will work. According to him, the regime is certainly feeling the heat. But “Chavismo” (named after Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chavez, another bete noire of the US) has had 27 years to embed itself in the country and will not easily be dislodged. Moreover, US interventions in Latin America do not have a great record of success. Shifter fears that what could happen is an internal struggle for power, destabilzing the entire region, and consuming the Trump administration for the rest of its term with the fall out.

The UK is not the only significant player to express reservations about the US’s approach. Canada has also reportedly suspended some cooperation, and Colombia, the latter on the grounds that it will not be party to human rights abuses, including against its citizens, some of whom have been killed in the boat attacks. This reflects wider tensions in the US-Colombia relationship, including a spectacular fallout between Colombia’s President, Gustavo Petro, and Trump personally, who ordered him to have his visa revoked and be removed from the US, during the UN General Assembly in New York, when Petro publicly urged members of the US National Guard not to comply with what he described as illegal orders by Trump to deploy in US cities.

The US administration has genuine grounds to be frustrated with Petro, under whose rule violence has returned to many parts of Colombia, and coca production reached unprecedented levels. In September, Washington “decertified” Bogota as an ally in combating drug trafficking. But, according to experts, Colombia is the source of over 80% of the US’s actionable intelligence on drugs in the region, meaning the loss of cooperation with it is way more harmful to US counternarcotics efforts than any suspension of UK assistance. Representative Gregory Meeks, the top Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, recently wrote to President Trump to express his strong concern about the national security implications of decertifying Colombia, and the importance of the U.S.-Colombia partnership for regional stability and security.

ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE? HELP US TO PRODUCE MORE

Receive the monthly Byline Times newspaper and help to support fearless, independent journalism that breaks stories, shapes the agenda and holds power to account.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.

According to the Hill newspaper, a number of Democrats and even some Republican members of Congress have expressed concern about the legal justification for the strikes, and whether the US is gearing up for military action inside Venezuela, which they argue should require authorization from Congress. The administration has provided several briefings to lawmakers to explain how targets are selected, but argued that the operations so far do not rise to the level of hostilities which would warrant seeking permission from the legislature.

Several defense officials have also expressed scepticism about the campaign, with the Commander of US South Com, Admiral Alvin Holsey, reportedly deciding to step down just one year into his tenure due to his concerns about the legality of the strikes.

The UK has not denied the media reports about its suspension of intelligence cooperation, with a government spokesperson merely stating that “it is our longstanding policy not to comment on intelligence matters.” A Pentagon official also reportedly told CNN that the department “does not talk about intelligence matters.” Working level officials on both sides are probably keen to squash the story, to prevent a bigger fall-out which could jeopardise wider UK-US cooperation.

But, critics of the administration’s actions, including members of Congress, are bound to latch onto the news to bolster their own arguments that the administration is acting illegally.

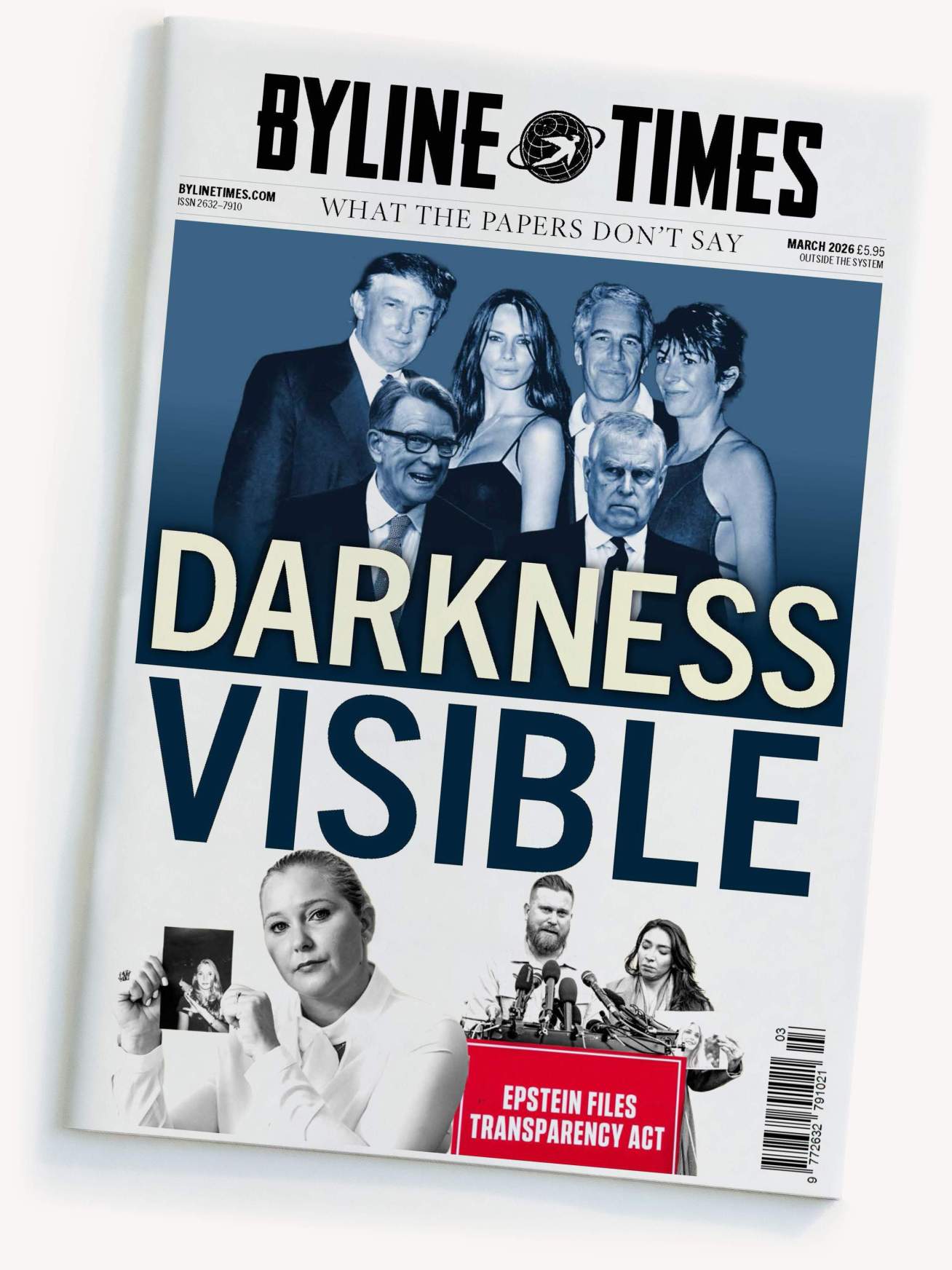

This could exacerbate tensions between the UK and the US at a more political level, fuelled by continuing stories drawing attention to the Epstein saga, concerning the former Prince, Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, the current row concerning the BBC, and wider policy debates over how to handle contentious matters such as Ukraine, Israel, and trade. There are many in his administration, such as JD Vance, who have not hesitated to voice criticism of the UK, for example, for allegedly suppressing freedom of speech, and mishandling immigration. The US’s main intelligence agencies are no longer led by consummate professionals, but by Trump toadies, such as FBI head Kash Patel, who value their personal relationship with Trump, more than the US’s strategic partnerships with its allies.

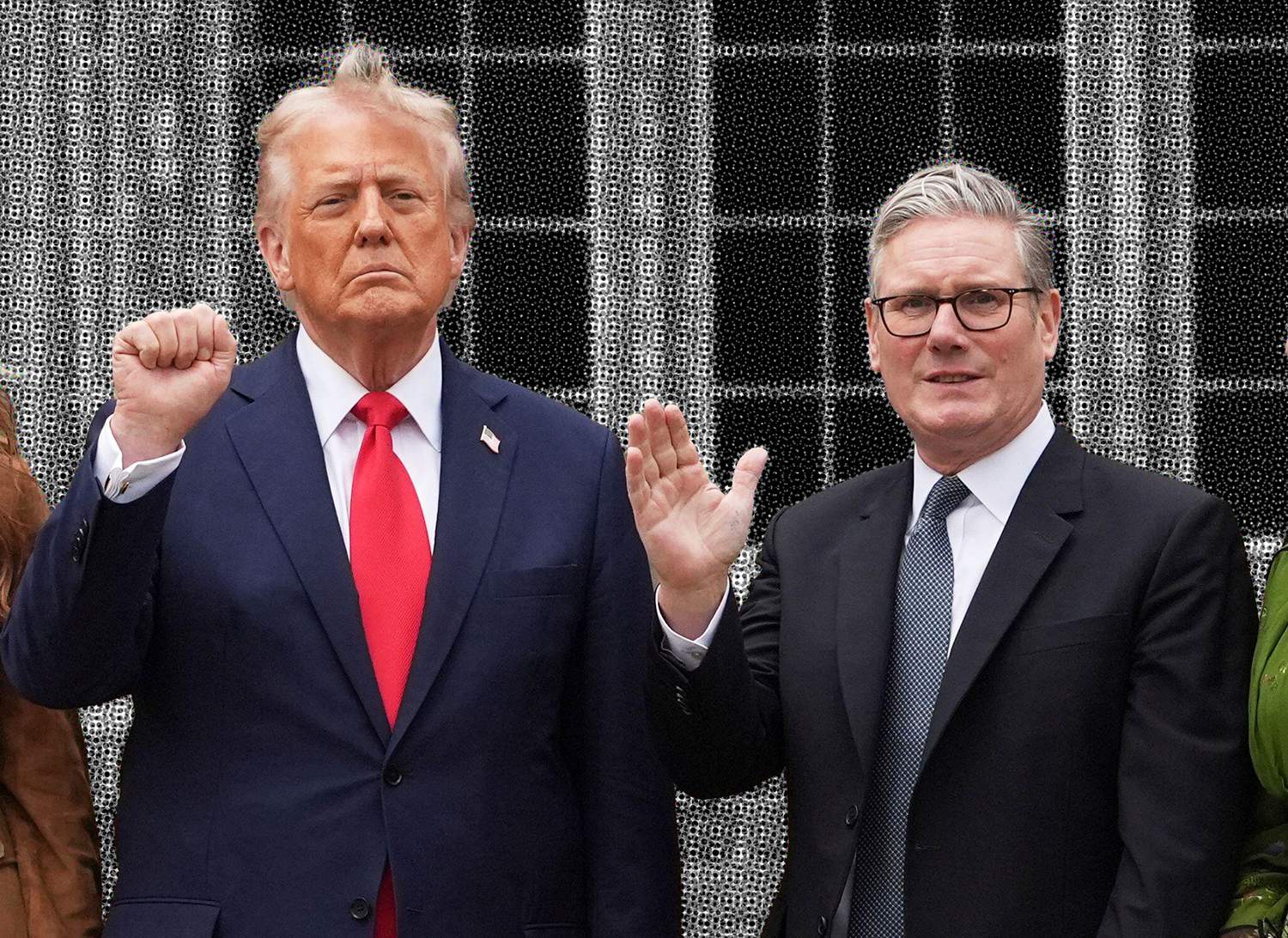

Up till now, Starmer has managed to maintain a cordial, even friendly relationship, with Trump, and been able to draw on lingering goodwill from the State Visit in September. But, Trump is notoriously touchy and fickle, particularly where he feels his own personal reputation is at stake. His admiration for Starmer also appeared to originate from the latter’s stunning electoral victory in 2024. Now that Starmer is stumbling in the polls, and facing rumours of internal Labour Party opposition, Trump may regard him as weak and vulnerable. Starmer, in turn, may face increasing pressure from the left in his party to stand up to Trump, including over the BBC row.

It remains strongly in the strategic interests of both countries not to let this bilateral matter escalate. But, given the wider political tensions and personalities involved, it cannot be ruled out.