Support our mission to provide fearless stories about and outside the media system

Read our

Digital / Print Editions

Packed with exclusive investigations, analysis, and features

Reform’s Promise

It sounds simple, almost seductive. Scrap “illegal migration”, close the hotels, deport those with no right to be here – and save taxpayers £42 billion over the next decade and £243bn over 80 years. That’s the promise Reform UK makes the centrepiece of its immigration policy.

But the OBR has already shown that drastic cuts to migration will be net negative for the economy. We build on this analysis to show how Reform UK’s own numbers reveal not hundreds of billions of savings, but a trillion pound blackhole.

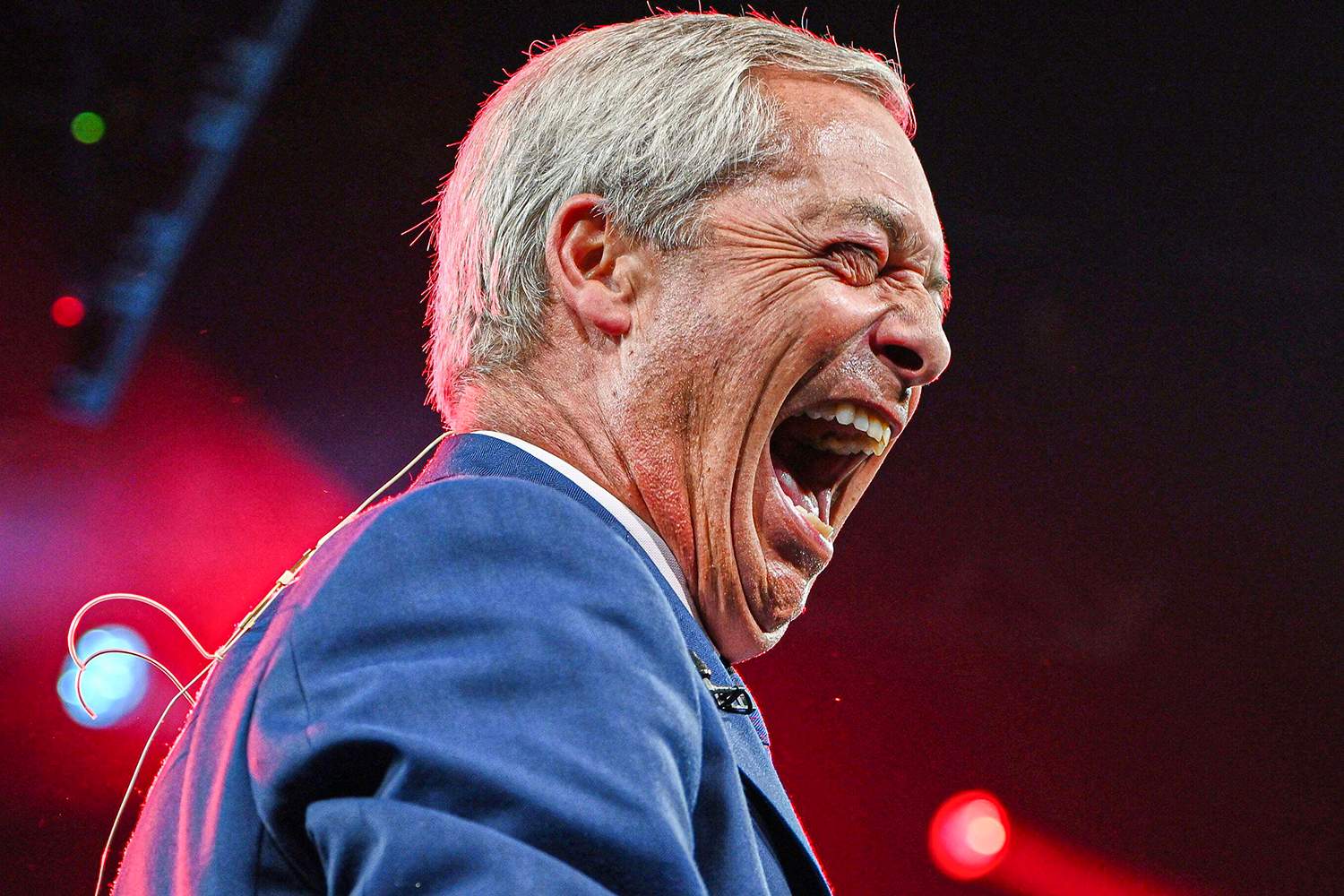

Nigel Farage’s previous pledge for a hard Brexit led to trade frictions, reduced labour mobility, and low investment – and shattered EU agreements that had kept the small boats crisis at bay.

Now, our analysis suggests his new plan would strike a further blow to Britain’s teetering economy.

In its official blueprint, Operation Restoring Justice, the party pledges to “end illegal migration” by ripping up Britain’s obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the Refugee Convention, pushing through a new “Mass Deportation Bill”, and creating a new UK Deportation Command.

Within 18 months, they say, Britain would have 24,000 new detention places and be running up to five deportation flights every day. Offshore camps on Ascension Island are floated as a fallback.

Their document claims the plan would save taxpayers “over £7 billion in five years” and £42 billion in a decade – money they say is currently squandered on asylum seekers in hotels.

The Reality

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) – the body that audits the public finances – concludes the opposite. In its March 2024 outlook, the OBR shows that cutting net migration raises Government borrowing by around £13-20 billion within five years, because migrants are mostly of prime working age, pay about £19,500 per adult per year in taxes, and generate £4.1bn a year in visa fees and surcharges.

In short, lower migration worsens the public finances, not the reverse.

Byline Times stress-tested Reform UK’s numbers against the OBR’s modelling. We found that instead of delivering a £42 billion windfall over a decade, the plan generates the opposite.

We found that over five years, the economy would be about £49bn smaller, while the Home Office would face £7bn in direct costs for detention, flights and enforcement, according to analysis of OBR projections.

The smaller economy also implies a £17bn shortfall in tax receipts, but this is a fiscal consequence of the GDP loss. Projected forward, by 2035, the drag rises to an economy £63-81bn smaller, plus £4-10bn in direct Exchequer costs, with £23-29bn less tax revenue embedded in the GDP loss.

ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE? HELP US TO PRODUCE MORE

Receive the monthly Byline Times newspaper and help to support fearless, independent journalism that breaks stories, shapes the agenda and holds power to account.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.

Farage claimed that their plan would save £234 billion over the lifetime of the average migrant (around 80 years), a figure taken from the Thatcherite think tank, the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS). However, the CPS later withdrew the figures as “erroneous”. Pressed about this, Farage doubled down, insisting the real savings would be even higher.

We do not believe it’s very meaningful to project, as Reform has, over an 80-year period due to the impossibility of incorporating the innumerable factors that can change in such a time-frame. But if we are to do so, over an 80 year period the total losses to the British economy wrought by Reform UK’s plan would amount to up to 2 trillion pounds – a conclusion consistent with the OBR’s modelling.

According to Jonathan Portes, Professor of Economics at King’s College London and a former chief economist at the Cabinet Office and Department of Work & Pensions: “Recent migrants have high employment rates and their earnings rise as they progress in the UK labour market. While the exact numbers are highly uncertain, Reform’s proposals to kick out people who came here legally to work and contribute would have a significant long-term economic and fiscal cost. They are a toxic cocktail of xenophobia and economic illiteracy.”

Follow the Money: Britain’s New Deportation Machine

Reform’s plan has the pace and scale of a military mobilisation. Within 18 months, they promise, Britain would have created 24,000 new detention places, a deportation force ready to seize and escort people at any hour, and up to five planes a day ferrying migrants out of the country.

It sounds decisive. But there’s one question the party never answers: who pays?

Detention: The £1 Billion Bed Bill

At present, Britain’s immigration estate holds fewer than 2,000 people at any one time. Reform wants to expand that to 24,000.

The Home Office’s own figures show that each detention place costs £122 per person, per day. Fill 24,000 beds at 90% occupancy and you are looking at nearly £1 billion every year just to keep the system running. That’s before you pay a penny in capital costs.

The Government has already spent tens of millions converting RAF sites at Wethersfield and Scampton into makeshift accommodation camps. The Foreign Office has warned that offshore processing, like the mooted camps on Ascension Island, would cost around £220 million per 1,000 beds.

At those rates, creating 24,000 places could swallow £5 billion or more in capital before a single person is deported.

Flights: Five Planes a Day

Reform promises five deportation flights every day. Picture that: a plane leaving Heathrow, Gatwick, Stansted, Luton, and Birmingham, day after day, year after year.

But removals are costly. An inspection in 2013 put the average cost at £15,000 per person. Rwanda flights cost £11,000 per head in aviation alone. Even on a conservative £5,000 per removal, the central throughput of 10,000 removals a month (around 600,000 over five years) implies £0.6bn a year in aviation and escort costs — higher if throughput or per‑person costs rise.

holding farage to account #reformUNCOVERED

While most the rest of the media seems to happy to give the handful of Reform MPs undue prominence, Byline Times is committed to tracking the activities of Nigel Farage’s party when actually in power

Enforcement: A Deportation Army

Mass removals need boots on the ground. Today’s immigration enforcement budget is around £482 million a year. Reform’s system would need thousands more staff: detention officers, escorts, caseworkers, lawyers.

That is not just an expansion. It is the creation of a new deportation army, costing at least £500 million annually in payroll and overheads.

Legal Risks and Offshore Deals

The Home Office already pays £12 million a year in compensation for unlawful detention. With indefinite detention and tens of thousands more detainees, payouts could multiply.

And then there are the offshore deals to send people to “safe” third countries. The Rwanda partnership was cancelled in July 2024 before any removal flights took place, after the Supreme Court found the plan unlawful; the National Audit Office had already logged £370m committed plus high per-person costs (£150k per person for processing and operational costs, plus a £20,000 transfer payment).

Scaling that model up would dwarf even current costs.

Even before you count this machinery, the OBR shows lower migration raises government borrowing; add these bills on top and Reform’s savings claim collapses further.

The Mirage of ‘Savings’

The National Audit Office found asylum accommodation contracts now total £15.3 billion over ten years, with hotels costing around £1.3 billion annually.

This is Reform’s jackpot. Shut the hotels, they say, and save the money.

But detention costs more. At £122 per day, 24,000 beds cost £1 billion a year — the same as hotels, with added bills for guards, lawyers, and flights. Reform’s plan swaps hotels for handcuffs, not savings.

The OBR’s March 2024 analysis shows migrants are net contributors to the public finances; cutting numbers pushes borrowing up. Even if hotels were closed tomorrow, detention costs do not vanish — and you also forego the tax and fee income the OBR counts on.

Reform also proposes abolishing Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR), replacing it with short, renewable visas. The OBR’s fiscal modelling implicitly assumes that many migrants stay, work and keep paying taxes over time. Remove permanence and you shorten working-life contributions, raise churn and training costs for employers, and reduce long-run receipts. That makes the fiscal damage worse than the OBR’s low-migration scenario — even before the costs of detention and flights.

Offshore processing is even worse. The Rwanda deal proves that far from being cheap, third-country arrangements are among the most expensive immigration policies ever tried.

To get to £42 billion, Reform essentially assumes that:

- Hotels close overnight and detention is free

- Offshore deals cost peanuts

- Every deportation is instant

- Deterrence magically stops the boats — despite the National Audit Office confirming there is no evidence harsh policies reduce arrivals

None of this is realistic.

The Fallout in Everyday Life

The bigger shock comes not from Home Office spreadsheets, but from ripping workers out of the economy.

The Migration Observatory warns that estimating the number of people in the UK without legal status is difficult due to uncertainties in the available data. The range appears to be between 600,000 and 900,000 people. If just 60% are working, Reform’s plan would remove 300,000-500,000 workers over five years.

These are not abstract numbers. They are the waiter serving your lunch, the cleaner at your office, the builder on your street, the carer looking after your mother.

- Hospitality: Labour shortages push up wages and prices. With restaurants & hotels making up 11% of the inflation basket, that feeds directly into inflation

- Construction: In London, nearly half of builders are foreign-born

- Fewer workers mean fewer homes, higher rents, and stalled net-zero projects

- Social care: Already 131,000 vacancies. When carers are short, NHS beds remain blocked — at £395 a day each

The OBR expects net migration to average 350,000 a year over the forecast horizon, adding roughly 300,000 working-age adults by 2029. That increase in labour supply is baked into its growth and borrowing forecasts. Remove those workers — or deny them permanence by scrapping ILR — and the OBR’s abstract numbers become painfully concrete: fewer carers and builders, higher prices, slower housebuilding, and higher borrowing.

Economically, the impact is brutal. At around £45,000 output per worker, removing 300,000-500,000 workers shrinks GDP by £10-23 billion annually.

By Year 5, the economy would be around £49bn smaller, with an implied tax shortfall of about £17bn. On top of that, the Home Office would face £7bn in direct costs for detention, flights and enforcement.

For the public finances, what matters is the net borrowing effect once lower revenues and lower spending are both taken into account. The OBR estimates that if net migration were cut by 200,000 a year — about 1 million fewer people over five years — Government borrowing would be £13-20bn higher by 2028-29.

Our scenario is deliberately conservative. We assume 300-500k removals over the same horizon, implying a GDP drag of 0.7–1% (compared with the OBR’s elasticity of 1.5% of GDP per 1 million migrants). The direction is the same: lower migration worsens growth and borrowing. Our analysis simply adds the extra bills Reform never mentions — the cost of detention estates, deportation flights and enforcement staff.

FUND MORE INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING

Help expose the big scandals of our era.

The Long Game

Stretch the horizon to ten years and the contradiction becomes starker. Reform claims £42 billion saved over that period. In reality, extending our five-year calculations forward shows Britain ends up even poorer.

By 2035, the economy would be £63-81bn smaller, while the Home Office would face £4-10bn in direct costs for detention, flights and enforcement. For the public finances, what matters is the net borrowing effect once lower revenues and lower spending are both taken into account. On this measure, the OBR estimates that lower migration leaves borrowing £13-20bn a year higher by 2028-29.

The OBR has already demonstrated the link between lower migration and higher borrowing. Our projection simply shows how that deterioration grows over a decade, once the costs of building and running a mass-deportation system are factored in.

The OBR’s modelling suggests that cutting net migration by one million people would mean about 700,000 fewer workers — roughly 1.5% of the labour force, and about 1.5% off GDP. Our scenario is more conservative: we assume 300,000 to 500,000 removals, with a slower productivity effect, which implies a GDP drag of about 0.7% to 1%.

The reason our overall figures are larger is that we are measuring something different: the OBR reports the net borrowing impact on the Government’s finances, while our analysis shows the wider GDP effect over multiple years plus the direct costs of mass deportation.

Beyond a Decade: A Generational Bill

Reform UK sells its plan as a one-off fix: spend a little now, save £42 billion in the long run. But economic damage doesn’t work like that.

When you strip 300,000-500,000 workers out of the economy, you don’t just lose their wages and output for a single year. You permanently shrink the base of the economy that future growth builds on. Investment decisions, tax revenues, and productivity improvements all flow from that smaller base.

Although GDP grows year after year — with fewer workers, it grows from a lower starting point. Each year’s growth compounds on that smaller base, so the gap between the economy we could have had and the one we are left with gets wider with every decade.

The OBR does not forecast beyond five years, but its assumptions are structural: migrants are mostly of working age, they participate more in the labour market, and they are net tax contributors. Those truths don’t expire in 2029. Extend them across a working lifetime and the effect is staggering. Even on static assumptions, the bill is £1 trillion in GDP loss; under the more realistic compounding path it rises to £2 trillion, with an embedded Treasury tax loss of £350-700bn. What the OBR flags as a £13-20bn annual borrowing deterioration in five years becomes, over decades, a generational black hole.

Think of it like a leak in a giant water tank:

At the start, the leak costs you about £13 billion a year in lost output (that’s the midpoint between our 5 and 10 year figures).

If the leak never got worse, then over 80 years you’d lose 80 buckets of £13 billion each. That adds up to just over £1 trillion.

This is the static scenario.

But in reality, the leak doesn’t stay constant — it grows with the size of the tank:

Britain’s economy normally gets bigger every year. When you’ve permanently removed hundreds of thousands of workers, the economy grows from a smaller base each year. That means the gap versus the “no deportation plan” economy widens every year.

So instead of losing the same £13 billion annually, the losses themselves get larger: £13 billion in the first year, a bit more the next, and so on. Even if the gap grows at only about 1.5% a year (the UK’s long-term trend growth), then after 80 years the cumulative loss is closer to £2 trillion.

This is the compounding “realistic” scenario over an 80-year horizon — the span of a migrant’s working lifetime:

- Static (floor):

Around £1 trillion in cumulative GDP loss over 80 years. £50-80bn in direct fiscal costs for detention and enforcement. The smaller economy implies £350-400bn less tax revenue, but this is already part of the GDP effect. The OBR would treat the Exchequer impact as a net borrowing shortfall.

- Compounding (realistic):

Around £2 trillion in cumulative GDP loss if the drag compounds, plus £50-80bn in direct fiscal costs. Within that GDP loss, the Treasury’s receipts would be £700bn+ lower over a lifetime. Again, this should be seen as the fiscal consequence of a smaller economy.

The compounding view is more realistic, because that’s how economies actually behave. Lost workers mean less output today, but also less investment tomorrow, weaker productivity growth, and lower tax revenues to fund schools, hospitals and infrastructure. Those missed opportunities don’t just vanish — they ripple forward, year after year.

Of course, we cannot precisely predict 80 years into the future with this data because over that period of time a myriad of issues may change: migration policy may be adjusted, technology may transform labour markets, and so on.

But this exercise allows us to follow through plausibly with the implications if Reform UK’s plan was stringently followed through without other complicating factors. And the upshot is clear: policies that deliberately shrink the workforce in essential sectors create a permanent drag on the economy. That drag compounds. It doesn’t just hurt today’s economy — it hands the next generation a smaller, weaker inheritance.

Instead of £42 billion “saved”, Reform’s plan risks an entire century of lost prosperity — a multi-trillion-pound mistake that grows larger with every passing year.