Read our Monthly Magazine

And support our mission to provide fearless stories about and outside the media system

Does he really think we’ll believe it?

It was the question that sat in our heads as we watched the then Prince Andrew give his fateful interview to Newsnight’s Emily Maitlis on his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein in 2019, months after the sex offender and trafficker was found dead in a New York prison.

Does he really think we’ll believe that he couldn’t have danced with a 17-year-old Virginia Giuffre in Tramp nightclub in London because he lost the ability to sweat during the Falklands War?

That he never met her because he was actually visiting a Pizza Express in Woking that night, which was “a very unusual thing” for someone like him to do?

That he only knew Epstein through his friend, and Epstein’s partner, Ghislaine Maxwell, even though he stayed at Epstein’s New York townhouse after his first conviction and was a guest-of-honour at a dinner party during the visit?

That Andrew has a “tendency to be too honourable”, and that was why he decided to visit Epstein in person to tell him it was “inappropriate for us to be seen together” again?

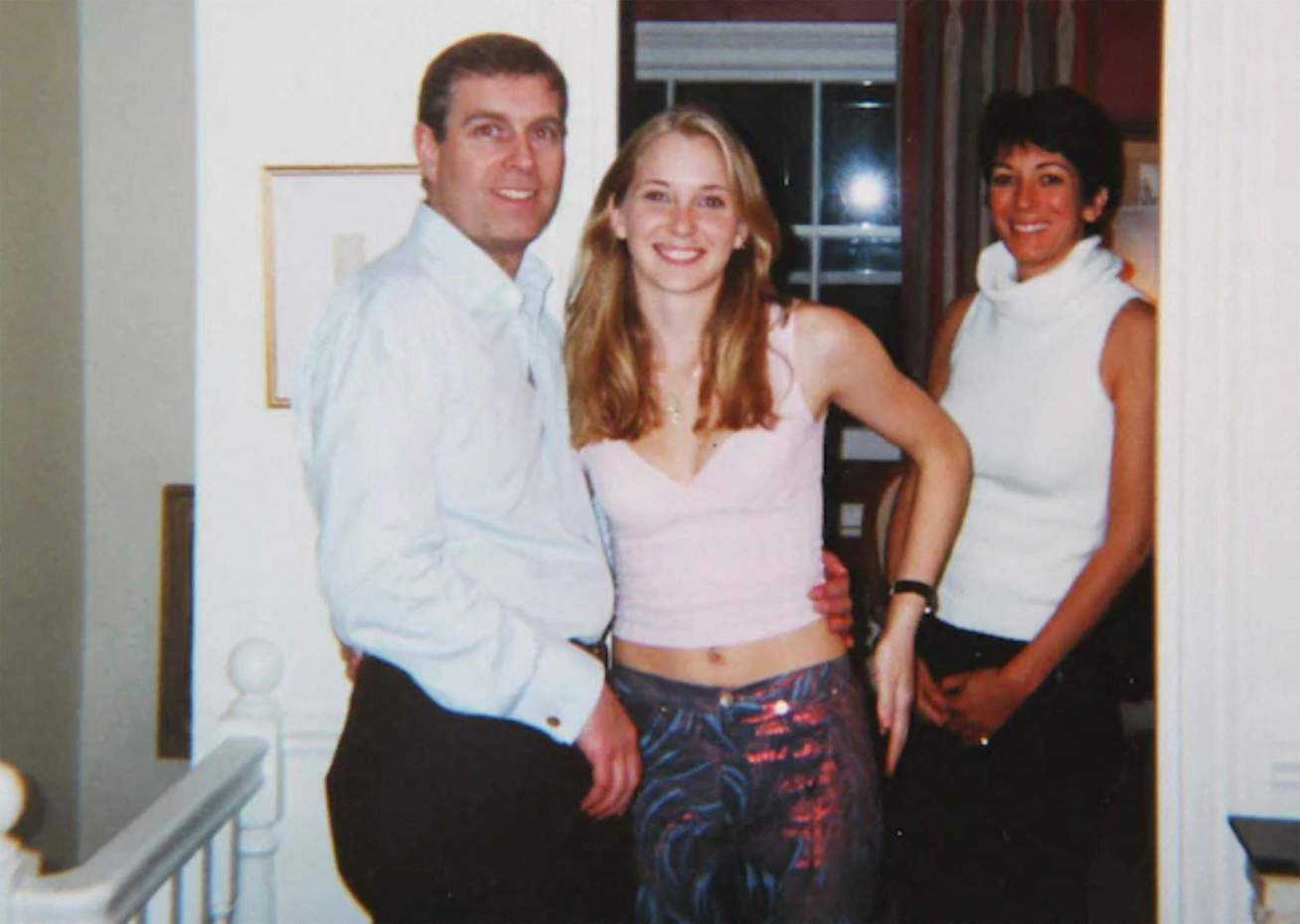

That a strong, smart adult woman who recounted, in detail, how she was trafficked to have sex with Andrew on three occasions as a teenager, had faked a photo of them posing together with Andrew’s hand on her side and Maxwell lurking madame-like in the background?

“Why would somebody have put in another hand?” Maitlis observed.

The answer is that Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor expected us to swallow it all, even if he didn’t think we would believe it.

This is laid bare by the release of the latest Epstein Files, which include photographs of the late Queen’s favourite son on all fours crawling above a woman lying on the floor.

It is confirmation of how the powerful protect their impunity through contempt for those they seek to exploit and manipulate.

Even if his litany of explanations about never meeting Virginia Giuffre sounded highly implausible – and the dogs in the street knew they were, frankly, ridiculous – Andrew expected the public to simply accept that he was providing an alternative account of these matters. It was enough that he was casting doubt on Virginia Giuffre’s sworn testimony in a US legal deposition, which states that he raped her.

Like other men with no connection to the real world most of us live in, accountability and exposure remain abstract notions; darkness becoming visible a distant and unlikely turn of events.

But no longer.

Among the three million items included in the last Epstein Files is an email headed “draft statement” sent by “G Maxwell” to Epstein in 2015. In it, she wrote: “In 2001, I was in London when [redacted] met a number of friends of mine, including Prince Andrew. A photograph was taken as I imagine she wanted to show it to friends and family.”

What we all knew in our gut, was what was clearly the truth.

Virginia Giuffre’s brother, Sky Roberts, has said the email shows his sister – who took her life last year – “was not lying this entire time”.

“It is a vindicating moment but we also want to use this as a moment to remind people to believe survivors… to take a look in the mirror and ask ourselves: what have we missed this entire time?” he added. “Why didn’t we believe this truth-teller?”

Any of us who have read Virginia Giuffre’s memoir, Nobody’s Girl; saw her recall her meetings with Andrew with specificity in interviews; read of the reportedly £12 million settlement he made to her over a civil sexual abuse lawsuit; or watched him – oblivious and haughty sat in Buckingham Palace – saying he had “never” met her and had no regrets about his friendship with Epstein on Newsnight knew that Virginia Giuffre was not lying.

In her words, “he knows exactly what he has done”.

But because the powerful believe there will be no consequences, and rely on the public believing that their impunity cannot be checked, we all (have to) go along with this systemic denial – the perpetrators, the public, and the survivors who must live with the truth.

Five months after Andrew’s interview with Emily Maitlis, I spent a weekend reading Svetlana Alexievich’s Second-Hand Time during lockdown. The pandemic had arrived in Britain, and it was a good time to take in her sprawling, extraordinary mosaic of the voices of those who had lived through the collapse of the Soviet Union.

One short account stayed with me as I watched the Government’s daily Coronavirus briefing that evening: “We lived our Soviet lives by a unified set of rules that applied to everyone. Someone stands at the podium. He lies, everyone applauds, but everyone knows that he’s lying and he knows that they know that he’s lying. Still, he says all that stuff and enjoys the applause.”

After watching the briefing, I wrote in a state of urgency an editorial published in these pages six years ago – about the dangers of living in a political culture in which those in positions of power rely on the expectation that they will mislead and dodge accountability in their own interests, and that no other dialogue is possible, even as people die in a health emergency.

I explored how, in his 2005 book on the last generation of the Soviet Union, anthropologist Alexei Yurchak had argued that everyone knew the Soviet system was failing, but no one could imagine an alternative to it so ordinary people entered into a ‘play’ with those in power, to maintain a pretence of a normal society. Everyone knew it wasn’t real, but it was accepted as such. The society, Yurchak argued, was in a state of “hypernormalisation”.

This hypernormalisation is perhaps a defining feature of how political and elite power operates in the 21st Century.

Even if we question what we are being told, we do not expect much to be done about it. So we either accept that or – increasingly – switch off from it altogether. We detach and protect. We allow the contempt that power wields to make us powerless – not only through the structures we must live in, but in our sense of ourselves.

Three weeks after the Coronavirus briefing, this hypernormalisation was on display again when Dominic Cummings, the Prime Minister’s then chief advisor, sat at a trestle table in the gardens of Downing Street and told the public that he had not breached lockdown rules and had driven to Barnard Castle with his wife and child to test his eyesight. I still remember how I was sitting and what I felt when I heard this.

When I speak to people – of all different backgrounds – who tell me they have no interest in politics, in journalism, in voting, that we do not live in a democracy, I do not blame them.

When people are treated with contempt, they hold on to that contempt. And search for alternative ways of being.

It should not be a surprise that this dehumanising state of affairs – for that is what contempt is: a disregarding of one’s dignity – is something we want to turn our backs on.

But the dehumanisation is built on the paralysis caused by the perception of our powerlessness.

The release of the Epstein Files – through the tireless work of the survivors of Jeffrey Epstein’s horrific abuse and a handful of politicians willing to take a stand in Trump’s America – may show what we already know to be the case. But that we now know the extent to which this is true, that we can actually see it – typed up and photographed – is still a seminal moment.

It shows that the possibility of moving towards what is right exists, even if the spotlights shining on a dark path seem too few and far between.

The ‘never complain, never explain’ mantra of the British monarchy has been forced to – too late – reckon with the severity of Andrew’s actions. Having stripped him of his titles, King Charles now says he is “ready to support” the police with any investigation; while US law-makers have said Andrew should testify in the United States over the Epstein Files.

Justice may yet be hard-won, but the modus operandi of contempt and powerlessness which the powerful rely on to sustain their corruptions has been exposed.

Nobody “put in another hand” in that photo. We always knew they didn’t.

Holding on to small and significant truths in our lives, especially when this is difficult, can make all the difference.

It was what Virginia Giuffre did, at huge personal cost, because she had no other choice.

Because of her, and the unwavering conviction of the other survivors of Jeffrey Epstein’s abuse, Donald Trump’s Government was forced to pass the Epstein Files Transparency Act.

They made darkness visible for us all.

Hardeep Matharu is the Editor-in-Chief of Byline Times