Read our Monthly Magazine

And support our mission to provide fearless stories about and outside the media system

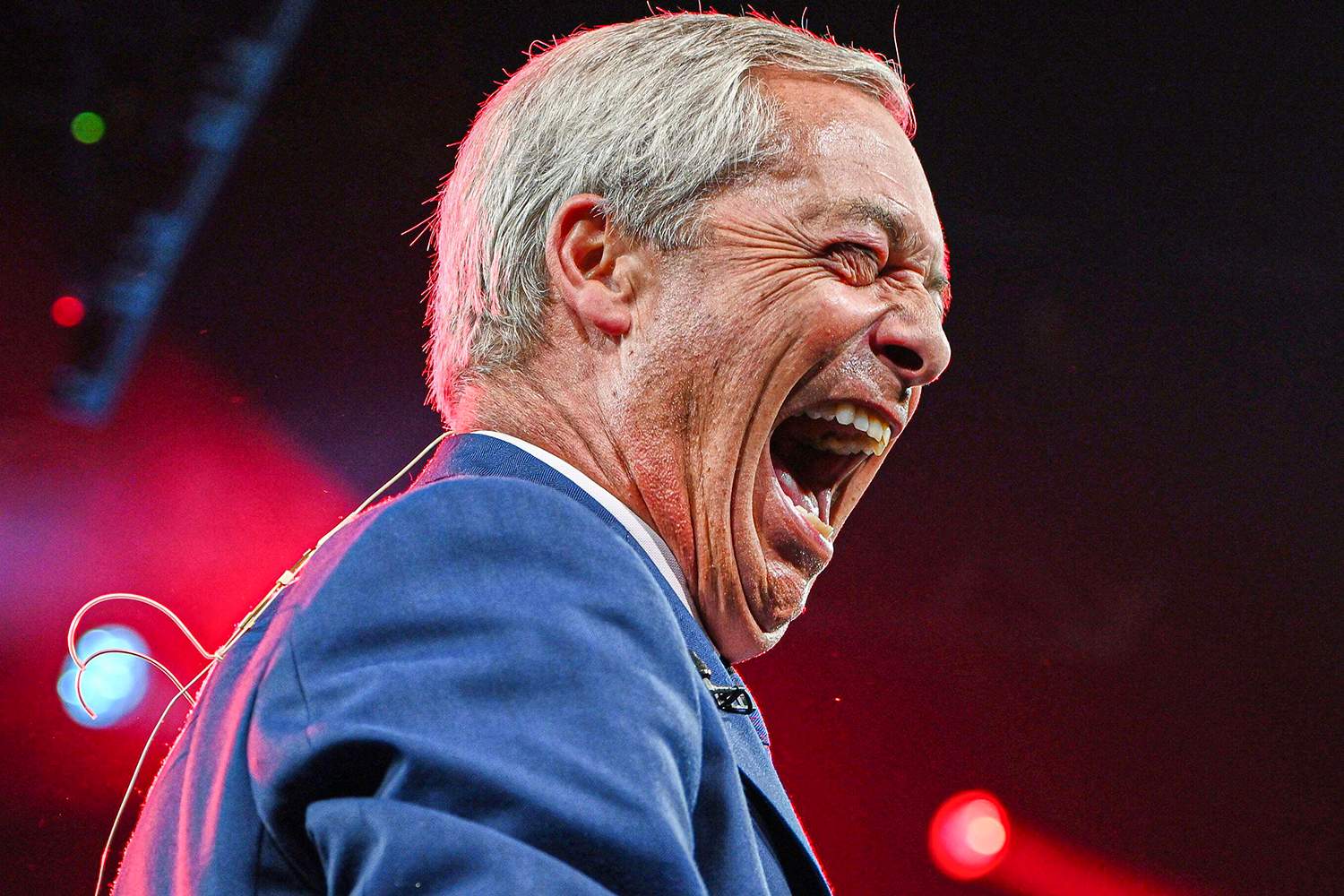

Nigel Farage on Monday announced plans to deport hundreds of thousands of people living and working legally in the UK.

His plan to force those already granted indefinite leave to remain, to reapply under much stricter rules would put the future of many thousands of our neighbours, relatives, friends and colleagues in doubt.

Across the UK thousands of families, communities, public services and businesses would risk being torn apart.

Almost nobody would be spared from the plan. Thousands of Ukrainians given refuge from Putin’s invading armies would face having to return, as would the thousands of people welcomed from Hong Kong. Nor would there be any exceptions for those who have lived here happily and legally for decades.

Under his plans even those granted leave to stay by a Farage-led Government could lose their right to benefits, NHS care and other support.

It is, in short, an abomination, and an abomination which if the polls are to be believed, could be heading our way in just a few short years time.

The plan did receive immediate condemnation from some quarters. London’s Labour Mayor Sadiq Khan, described it as “unacceptable” saying “they have legal rights and are our friends, neighbours and colleagues, contributing hugely to our city.”

“Threatening to deport people living and working here legally is unacceptable.”

A handful of Labour backbenchers publicly agreed, with Labour MP Sarah Owen condemning it as “morally abhorrent” and “dangerous”.

Yet to listen to the actual Government and its representatives today, you would get the impression that the real problem with the policy is merely an administrative one.

Asked what the Prime Minister’s response was to the proposal, a spokesperson for Keir Starmer would say only that he thought it was “unworkable”, “unrealistic” and “unfunded”.

Political spokespeople agreed, with Labour chair Anna Turley merely describing Farage’s mass deportation plans as “half baked” because they “rely on discredited numbers.”

“Reform have been forced to admit that their policy does not apply to people from the EU – destroying Farage’s claims that it covers all foreign-born nationals,” she said.

So no real condemnation of the principle of mass deporting hundreds of thousands of people, no real appeal to the people whose future is now in doubt, and no reassurance that their future will always be be secure under a Labour Government.

For a Government led by a man who was elected as leader on an explicit pledge to “defend migrant rights” this feels like an incredibly weak response, yet it is by no means a new one.

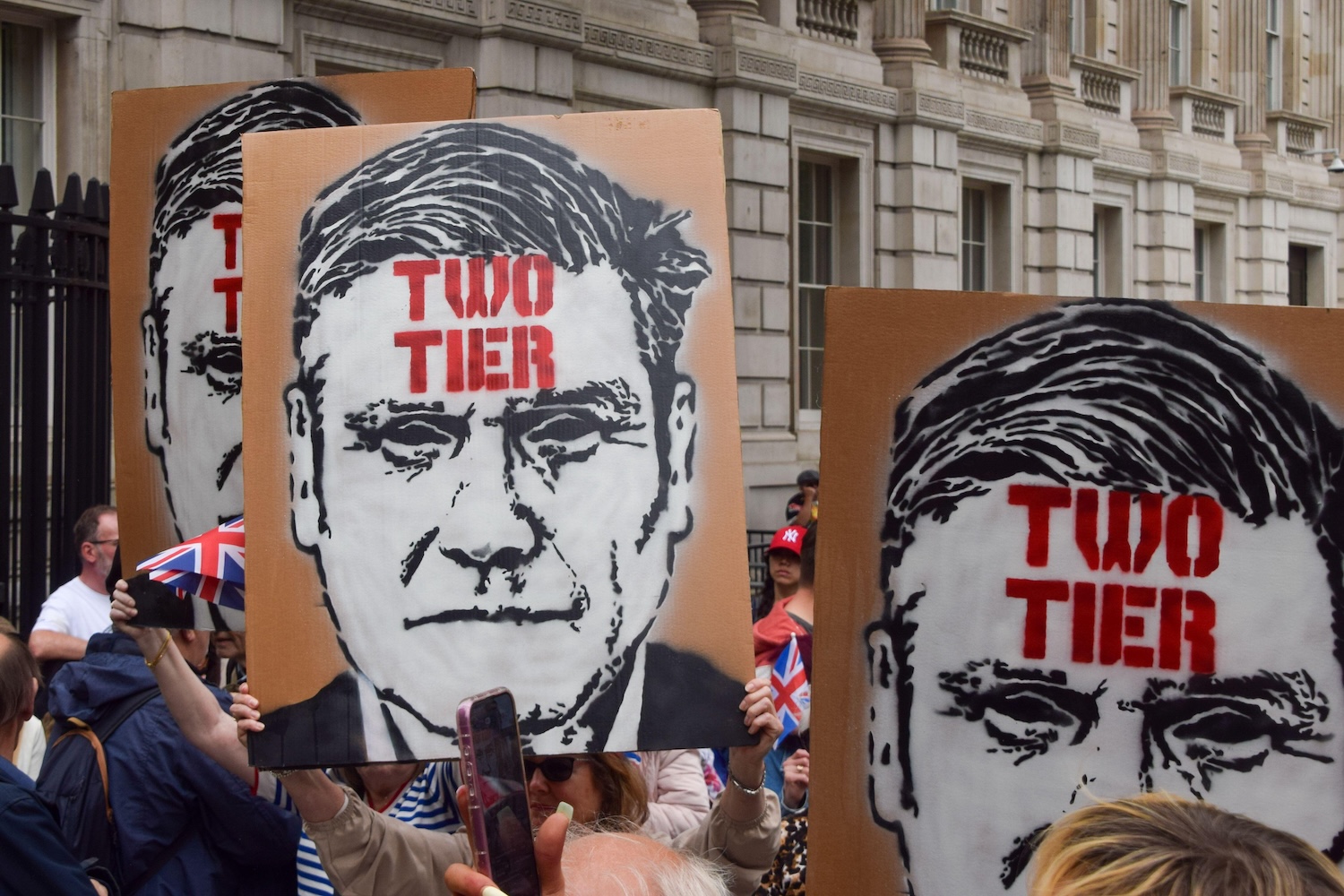

For years now Labour under Starmer has refused to explicitly condemn the lurch to the far-right taken by both Reform and the Conservatives on immigration.

When the last Conservative Government announced its plan to mass deport refugees to Rwanda, in order to end the “invasion on our southern coast” there was no explicit moral condemnation from Labour representatives, of either the rhetoric, or the principle.

Instead the party merely suggested that the plan was too expensive and unworkable. The exact same criticism they are now making of Farage’s plans for mass deportations of legal residents too.

ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE? HELP US TO PRODUCE MORE

Receive the monthly Byline Times newspaper and help to support fearless, independent journalism that breaks stories, shapes the agenda and holds power to account.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.

This is not an accident. Under the “Blue Labour” strategy of Starmer’s chief of staff Morgan McSweeney, any condemnation of anti-immigration politics as being immoral, or fundamentally wrong, is verboten. Instead such politics can only ever be criticised in practical terms as being either unworkable, unpractical, or worst of all “unfunded”.

Occasionally Government representatives are permitted to go slightly further, as they did today, by condemning their opponents for being “divisive”. Yet in doing so they merely further highlight their own reluctance to ever make an explicit moral judgement.

By saying something is “divisive” they dodge making a judgement about which side of that divide they come down upon. ‘Perhaps we agree with Farage’s view on mass deporting British resident, perhaps we don’t, but shouldn’t he just stop being so ‘divisive’?’ about it, they seem to say.

There are many problems with this approach. The first and most important is that it is a betrayal of the Labour party’s tradition of standing up for the marginalised and the oppressed. If a Labour Government led by a former Human Rights lawyer can’t explicitly condemn a plan for arbitrary mass deportations then what on earth can it do?

The second main problem is that it merely legitimises the arguments of their opponents. By refusing to ever criticise the anti-migrant politics of Reform and the Conservatives, while repeatedly flirting with such politics themselves, Starmer and his party are essentially conceding the argument to their opponents. A strategy of saying ‘Farage is basically right, but he’s not as competent as us’ is always going to be a losing one. Voters attracted to the anti-migrant politics of Farage are not likely to be won over by appeals for a weaker but more competent alternative.

It doesn’t have to be this way. While public anti-migration sentiment has been rising in recent months the sorts of proposals put forward by Farage would in practice likely be deeply unpopular. As we are already seeing in the United States, while many voters may support the idea of “sending them back” they often hate the reality of what that entails. Ask an average British person whether they want lower migration and they will probably agree, but ask them whether they want their friends, neighbours, colleagues, teachers and doctors woken in the dead of night to be bundled into vans and put on deportation planes and you are likely to get a very different response.

Similarly, while many voters may support the idea of deportations in the abstract, they are highly unlikely to support the reality of public services and businesses going to the wall due to staff shortages on a scale never before seen in the postwar era.

These may be difficult arguments for politicians to make but they are essential ones in order to prevent what would happen were Farage to ever get his way. By refusing to ever explicitly make them, Starmer and his Government are only increasing the likelihood that he one day will.