Read our Digital & Print Editions

And support our mission to provide fearless stories about and outside the media system

It was as I was reading the horrifying details of the Afghan data leak that I got the alert. ‘BBC BREAKING NEWS: Thousands of Afghans relocated to UK under secret government scheme after defence data breach’.

In a second, the BBC had taken a story about the UK endangering tens of thousands of Afghans – many of whom had worked for the British army – and made it a story about migrants breaching our borders. They had taken a story about the Government covering up its own mistake, and spun it into a woke refugee resettlement conspiracy!

So look. My uni history thesis re-examined accounts of colonial wars fought hundreds of years ago. I used local diaries to fact-check histories written by Western academics. But I shouldn’t have wasted my time crawling through archives – I could have run the same study on this week’s headlines. The racist and colonialist rewriting of warfare is still alive and well. Which brings us to today’s Media Storm: war reporting.

CNN’s chief international anchor, Christiane Amanpour, had to be corrected live on air by The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart when she said: “Our major problem covering Israel-Gaza is that… journalists are not on the ground in Gaza.”

She had meant to condemn Israel’s ban on international journalists – instead, she condemned herself. There are, of course, journalists on the ground in Gaza, and more of them have been murdered than in any other war on record.

The far more accurate diagnosis of the problem came from one of them, Hossam Shabat: “The problem is not Western journalists being unable to enter, but the fact that Western media doesn’t respect and value Palestinian journalists.”

Local reporters are often overlooked (even without a strategised campaign to smear them all as Hamas operatives), but the hidden hierarchies of war reporting run deeper.

I first heard the term ‘fixer’ during my journalism Masters. Yet I had met a fixer before, while working in the refugee camps on France’s UK-facing coast. He was an Afghan man and had worked for British journalists covering their army’s invasion of his country.

When he became targeted by the Taliban as a “collaborator for the enemy”, he fled. The fixer told me this story after arriving in Dunkirk in the middle of that harsh 2017 winter, and I added his name to my ‘try find him a tent’ list.

We were short of supplies a year after the demolition of the ‘Jungle’ camp (just another failed attempt to erase ‘the refugee problem’ from our shores). I nicknamed the remaining wasteland ‘the elephant on the doorstep’. People who had helped Britain were ignored.

When I later learned the term ‘fixer’, our lecturer explained that fixers are local experts who aid foreign journalists. They may find people to interview, earn their trust, or gain access to exclusive spaces. I remember thinking, isn’t that what we call ‘reporting’? It certainly is when Brits are doing it.

I have wanted to do this week’s Media Storm episode since we started the podcast four years and six series ago. The episode is about war reporters – those larger-than-life heroes who make gritty, complex, epic roles for A-listers like Rosamund Pike to win Oscars with – and fixers, their invisible enablers, who take on more of the risk for none of the recognition.

“We have many cases where fixers were either kidnapped or killed for their work,” Abeer Ayyoub, a former fixer from Gaza, told us.

Fifteen years later, Ayyoub is an established journalist based in Canada with an Oxford Reuters Institute fellowship under her belt. But back home, she was a fixer at the whim of foreign colleagues: “I worked on stories that I hated. I was taken to places I didn’t like”. All this, with no recognition – and consequently, no protection.

“I didn’t know that if I worked as a fixer on a story, I could ask for a byline. I would accept any amount of money, and I never got the privilege to ask for security,” she said.

Fixers don’t know their rights. But the sad part is it should be the media outlets that recognise their rights without them asking.

Abeer Ayyoub, journalist

A ‘byline’ is a credit naming journalists at the top of an article, and in our trade, bylines are currency.

Fixers seldom get a byline, despite doing much of the labour. Why? “There’s a kind of arrogance – that war hero swagger – that comes with correspondents,” said our second guest, British foreign correspondent Phoebe Greenwood. “It would be a blindness, they wouldn’t necessarily see it.”

Greenwood has just published a novel called ‘Vulture’, a term used by war correspondents to cynically convey that they “chose to make their living out of other’s disasters”. She asks, “Why is it that largely white, middle class, privately educated people are telling other people’s stories, other people’s tragedies?”

“It’s different for me because I am from a conflict zone,” Ayyoub noted. “War reporting chose me. Not the other way around.”

To be clear, some of the most vital reporting is produced by foreign correspondents, and there are benefits to detachment.

“Sometimes when you’re up so close you can’t see the bigger picture,” Sky’s correspondent Alex Crawford, who has over 20 years experience as a foreign correspondent, told me.

Ayyoub confirmed she sometimes feels community pressure to report exclusively on Palestinian grievances. “It’s the balance between the expertise of the local and the foreign reporter that works,” she said. But the current hierarchy does not reflect this.

There is also a risk, when foreign journalists wade into conflict zones sniffing for a story, that the story becomes more important than the people living it.

You are arriving in the worst moment in that person’s life and trying to get a line out of them. That is such a deeply uncomfortable, unnatural position to be in

Phoebe Greenwood, British foreign correspondent

Grotesquely, Greenwood was once told by a documentary executive: “Just get me an execution because I can’t have any more stories about sad Mohammeds.”

Locals are often harmed by these practices. But the quality of the journalism suffers too.

Ayyoub told us a story about an interview she translated, between a British journalist and a Palestinian man facing conviction for involvement in a failed attack that Israel had classed as terrorism.

The journalist told her to ask him, “If you go back in time, would you still try to do a terrorist attack?” Ayyoub was horrified by the offensiveness of the question, and its futility in the context of such desperate violence, and of it coming out of her own mouth. She declined, but was told, “‘no, we need it for the story’”.

What if the story readers are being given is not what they need to know? Perhaps the foreign journalist genuinely believed the most relevant part of what happened that day was that the individual, now being punished for a failed attack, regretted it. But perhaps the local expert he ignored knew better.

“Anyone who doesn’t listen to the local journalist they’re working with, who knows the people and the story and the political landscape so much better, is not representing the people accurately,” said Greenwood. “They’re blinded by a myopic focus on the line they think they want to have. And you’re right, they’re just not getting the story!”

Western cultural and political bias is arguably the most pervasive and covert prejudice distorting the news we read, and it fundamentally hinders our ability to understand the vast majority of the world who see it so differently. In the context of foreign wars, this is particularly sinister.

“If you watch the coverage of the Gaza War today,” said Ayyoub, “it surprises me that some media outlets are still committed to this specific narrative. I know it’s not true, and they know it’s not true.”

But those outlets are no longer the ones most of us are relying on to tell us what is happening.

ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE? HELP US TO PRODUCE MORE

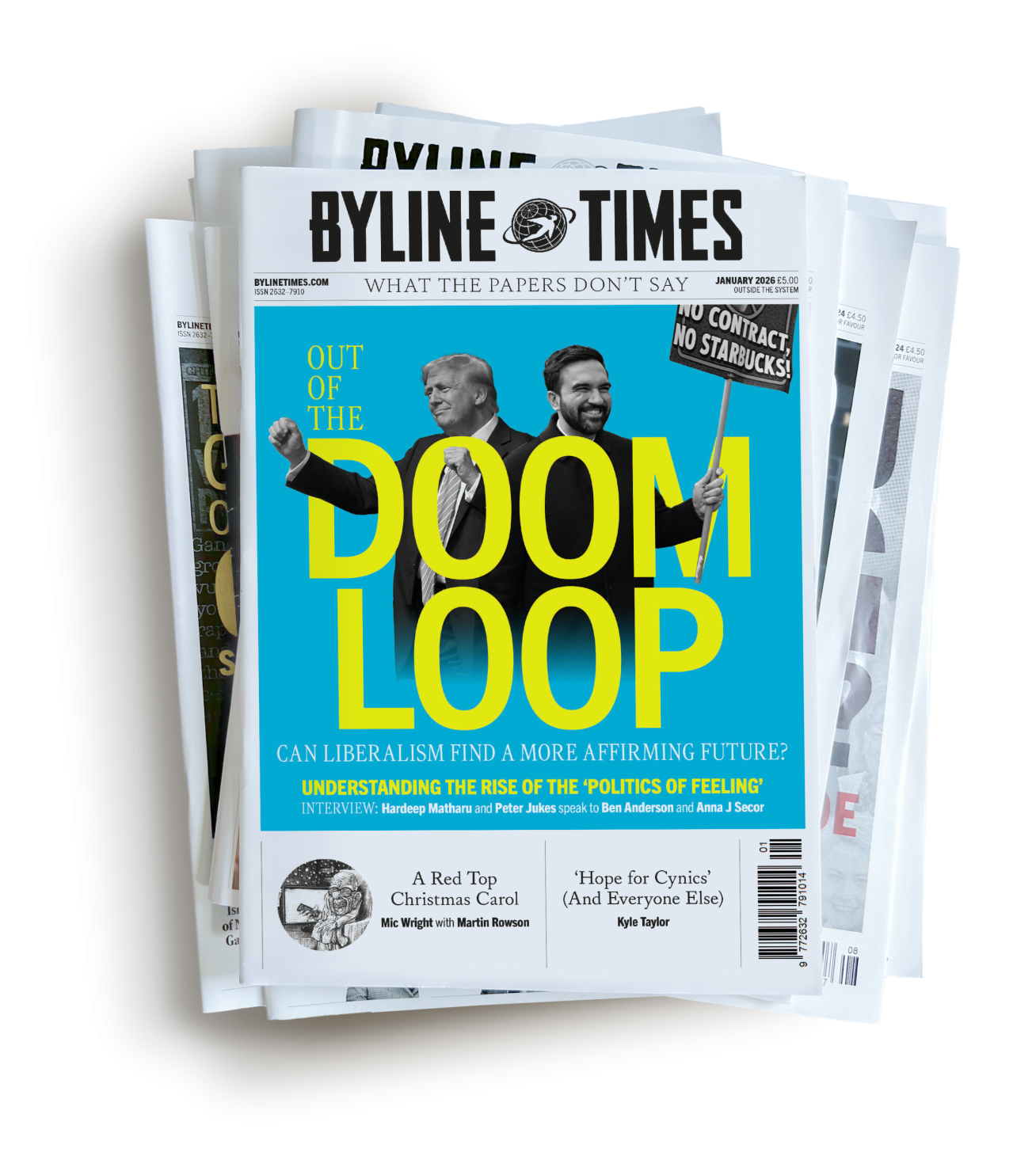

Receive the monthly Byline Times newspaper and help to support fearless, independent journalism that breaks stories, shapes the agenda and holds power to account.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.

“The way the war in Gaza has been covered in the media,” Greenwood reflected, “it’s going to take time to digest. However, it has to change things.”

“It has to change things that the only information that we receive from Gaza was from the Palestinians living it. People are digesting their information differently. And you can see the creaking mechanism of the old style of journalism really suffering in this conflict. Slowly the news organisations are going to have to catch up, and I think that allowing local people to tell local stories will be a huge part of that.”

Crawford concurred: “I think I’m probably a dying breed. Maybe the last of my kind, and maybe rightly so.”

Media Storm’s latest episode: War Reporters: White saviours or vital journalists’ is out now.