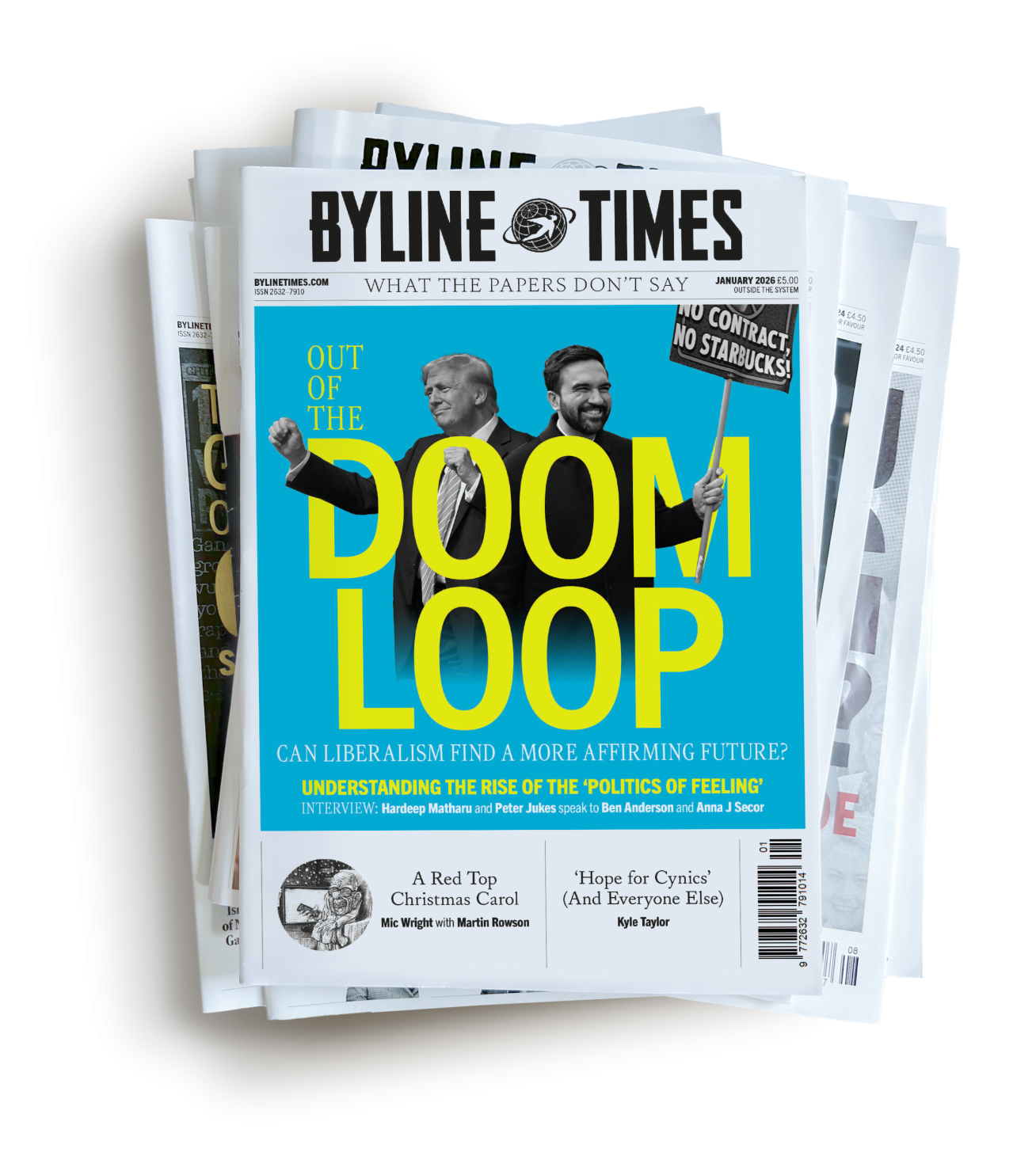

Read our Digital & Print Editions

And support our mission to provide fearless stories about and outside the media system

Over the past decade, we have witnessed a large-scale exodus of political opposition figures and civil society activists from Russia. This is not a spontaneous migration, nor one driven by personal ambition — it is a deliberate, strategically managed policy by the Kremlin to exile, neutralise, and effectively erase alternative political life within the country. The mechanism is not limited to prison sentences (although those remain a powerful tool), but also includes a subtler, more precise form of pressure that pushes people toward emigration.

Exile has long been a tool of the Russian state in its efforts to suppress what it perceives as “dangerous” intellectual or political energy. Tsar Nicholas I sent the Decembrists to Siberia. Under Nicholas II, there was mass emigration of socialist thinkers. In the Soviet era, the state expelled so-called “enemies of the people” — dissidents, physicists, philosophers, and former elites — or forced them to conform, collaborate, and eventually be destroyed by the system under Stalin’s rule.

Modern Russia has invented nothing new — it has simply digitised and legalised the machinery of exile. Today, the process is formalised through courts, amendments to the criminal code, and the branding of individuals as “foreign agents”. Most importantly, it manufactures a constant sense of vulnerability for anyone who dares to oppose Putin’s regime. The Kremlin no longer needs to eliminate an enemy immediately; it first isolates them, drives them out of the political and social landscape. Emigration becomes not an act of freedom, but a reaction to an engineered trap.

As the saying goes, Russia’s rulers have, for generations, expelled those who get in the way of their lies. Rather than seeking dialogue or fostering a system that accommodates differing political views — what we might ordinarily call democracy — the Kremlin has consciously chosen to divide society into “us” and “them”.

The Geography of Modern Russian Exile

According to independent estimates, hundreds of thousands of Russians have left the country since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The main waves of emigration have headed toward Georgia, Lithuania, Germany, Poland, and other European states. This is not an economic migration. These people are leaving for political reasons — driven by fear for their freedom, safety, and the protection of their families.

The largest and most distinct group consists of political activists, lawyers, journalists, and human rights defenders. These are individuals whose work involves protest, exposing corruption, defending victims of political persecution, and resisting authoritarianism — even within the boundaries of the existing legal system. They have faced a stark choice: remain and face repression, accept Putin’s political reality, or leave — forced into exile.

From my own experience working in the Navalny team in St. Petersburg, I saw the rise of a new, harsher system of political repression take shape. Lawyers, journalists, and activists quickly understood that even limited participation in anti-regime activity meant the end of any legal civic or political life in Russia. You would never again be allowed to run for office. You would not be permitted to register a political party. You would fail any application for civil service. And if you were already a government employee, you would soon be dismissed. And that was just the visible tip of the iceberg.

What began then has only intensified. The longer one remained publicly opposed to the regime — or even simply expressed support for opposition movements — the deeper the spiral of repression became.

By 2022, after the invasion of Ukraine, the pressure reached a breaking point. It became clear that even remaining silent could be grounds for persecution. I remember what I thought on the first day of the full-scale war: if Putin’s regime had made the decision to invade Ukraine, then they would have no hesitation in turning those same weapons inward — against their own citizens.

Over the past decade, Russia’s political system has shifted from authoritarianism with democratic façades to a fully-fledged repressive dictatorship. Its primary method of suppressing dissent is not just intimidation or imprisonment — but strategic expulsion.

Forced emigration has become the preferred tool. Those who refuse to remain silent are no longer executed en masse, as they were under Stalin, nor universally imprisoned, as in 1937 — though, if you examine the newly introduced criminal laws since the war began, we are dangerously close. Instead, they are pushed out — forced to live under the looming threat of arbitrary prosecution, with no way to continue life under the regime’s legal noose.

This policy allows the Kremlin to maintain a veneer of international legitimacy. Leaving “of your own accord” is not the same, on paper, as being thrown into a modern-day gulag. But in reality, the state has built a system of exile as a form of repression. It has its own architecture: laws, threats, and the deliberate dismantling of life’s basic infrastructure. This is not a side effect. It is a strategy.

The Machinery of Expulsion

The Kremlin’s strategy of forcing out opposition figures and civil society actors operates through a wide array of tools — from psychological pressure to direct threats to personal freedom. The process typically unfolds in the following phases:

Pre-emptive Fear

Many activists left Russia before any formal charges were filed or arrests made. They fled after receiving ominous phone calls at night, hearing rumours about potential criminal investigations, or learning that police had raided the homes of their friends. When you know you’re being watched, and political trials begin against people in your circle, you leave. This is a form of preventative state terror — repression without formal legal action, but with a clear message: you could be next. And your only “crime” is disagreeing with the Government.

Criminal Prosecution

Before the full-scale war in Ukraine, criminal cases against political opponents were a common, though not constant, method of repression. But since the invasion, all restraints seem to have disappeared. Prosecutions now appear arbitrary and chaotic.

Today, the logic is this: if you don’t leave after facing administrative penalties (which may include up to 30 days in detention or fines), then a criminal case is likely to follow swiftly. Charges are typically filed under broad, politically charged statutes: “spreading fake news about the Russian military”, “extremism”, “discrediting the armed forces”, or “participation in activities of an undesirable organisation”. In some cases, other, more mundane charges are used as legal smokescreens.

This legal arsenal is highly flexible. A Facebook post, a one-man protest, a donation to the “wrong” charity — all are grounds for prosecution. Hundreds of cases have been launched against individuals who did little more than publicly express a position. The number of such cases is already in the thousands. And that only includes those we know of — the ones who are already in prison. There are many more behind bars about whom nothing is known.

Take the case of Pavel Kushnir: until news of his death in pre-trial detention in Birobidzhan surfaced, no one even knew he’d been arrested. His supposed “crime”? Posting a video on YouTube — to an audience of just five subscribers — criticising the actions of the Russian military.

The State’s Toolkit: Institutionalised Fear

As the former head of Alexei Navalny’s campaign in St. Petersburg, I experienced the full spectrum of repression firsthand. Between 2017 and 2019, we built a grassroots campaign network involving tens of thousands of volunteers across the city. We operated within the law, called for peaceful action — but that made no difference.

We were met with escalating repression: repeated arrests (mine and those of our volunteers), office raids, threats, provocations, and fines amounting to tens of thousands of euros. At first, these obstacles didn’t stop us — but they made life in Russia increasingly volatile and unsustainable.

After Navalny’s poisoning in 2020, it became clear that we were next. We had the experience, the networks, and the ability to mobilise citizens — and that made us targets. In 2022, following the invasion of Ukraine, the FSB came to my home, conducted a search, and confiscated all my devices. I was held for several days in detention. After being released on a travel ban, I understood: staying would mean prison. It would mean silence. It would mean the end of my ability to help others.

FUND MORE INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING

Help expose the big scandals of our era.

I left for Poland and was granted international protection. Since then, I’ve dedicated myself to supporting other Russian refugees, coordinating legal aid, and documenting the repression we face — ensuring the world knows what is happening to those who refuse to submit to Putin’s political machine. Many of those forced into exile continue this work every day. They have not given up. They remain faithful to their principles.

Managed Chaos

The Kremlin is deliberately pursuing a strategy of suppressing domestic political engagement and civic activity.

Creating an environment within Russia that discourages protest has become a central tactic of the regime. Across the country — and especially in the regions — visible opposition has all but disappeared. The mass departure of politically minded citizens is not just a symptom of repression; it is now used as proof that “there is no opposition left”. Of course, many brave individuals still remain inside Russia, continuing to resist in subtle but meaningful ways — helping one another, holding on, and waiting for the moment when change becomes possible. But their lives are under constant threat.

For instance, the Russian authorities have recently launched a large-scale criminal investigation targeting individuals who donated to Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) between 2021 and 2022 — after it was declared an “extremist organisation”. Dozens of criminal cases have already been opened. People are being prosecuted for “financing extremist activity” — simply for making a donation.

Even more chilling: today in Russia, you can be prosecuted for displaying Navalny’s campaign logo or sharing a photo of him — now officially classified as extremist symbols.

In this context, remaining in Russia as a former supporter of the opposition — and particularly as someone involved in Navalny’s campaign — is extremely dangerous.

The Future of the Exiled

The flight of political activists from Russia should not be seen as a defeat. Rather, it represents a valuable resource — one that can and must be organised, modernised, and mobilised. These communities abroad could play a vital role in shaping the future of a post-Putin Russia.

The key task now is to build institutions and networks within the Russian diaspora — communities rich in political experience and capable of effective resistance to the Kremlin’s authoritarian machine. Russia has not disappeared. And Vladimir Putin continues to escalate risks, inching ever closer to the complete dismantling of the international security system — which, frankly, is already showing deep cracks.

Yet despite this, Russian diaspora communities remain largely excluded from global conversations about Russia’s future. This disconnect risks distorting the world’s understanding of what is happening — and what could happen.

The experience and unyielding stance of exiled Russians carry immense value. They represent a form of intellectual capital that must not be ignored. Their determination to stand against Putin — even from exile — is not only morally vital but strategically indispensable.

What Comes Next?

Historically, political exiles have often returned as architects of new systems — not just as critics of the past, but as keepers of memory, ideas, and democratic values. Poland offers a striking example. Today, the Third Polish Republic draws legitimacy and moral clarity from those who once resisted both Nazism and Communism. In honouring them, Poland laid the intellectual and institutional groundwork for its present-day democratic state.

We are seeing the early signs of such a legacy in the Russian exile community today. Independent media is emerging. Yulia Navalnaya has announced plans for a free satellite TV channel broadcasting into Russia. Legal aid centres and cultural initiatives are taking root. These efforts are laying the foundation for a Russia without Putin — not in the distant future, but right now.

But this potential cannot be realised without external support. Institutional, legal, and media backing is essential. The infrastructure of the exiled opposition must be supported and expanded — not as an act of charity, but as a strategic investment in Europe’s long-term security. We must build platforms for analysis, participation, and advocacy, and recognise those in exile not only as refugees — but as the political force of the future.

Without this support, there will be no democratic Russia tomorrow. And without a democratic Russia, European security will remain at risk.

The Russian state has mastered the use of political repression as a tool of control. But every person who has been forced to leave is not a failure of that system — they are a witness, a carrier of alternative values, and a builder of what comes next.

While the regime imprisons and silences those who believe in a different future, we — in exile — are building. While it censors, we speak. While it destroys, we piece together what has been broken. This is not just resistance — it is a deliberate, ongoing counter-strategy to authoritarian rule.

The Kremlin seeks to normalise exile — to make it mundane and invisible. But we must challenge this. We must reframe those who were forced to flee as guardians of memory and founders of new institutions. One day, they may help construct a free and flourishing Russia.

We were never advocates of reaction or repression. We stood for progress — for a better, freer future for our country.

And that is why I believe: history is on our side.

We have a chance.

ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE? HELP US TO PRODUCE MORE

Receive the monthly Byline Times newspaper and help to support fearless, independent journalism that breaks stories, shapes the agenda and holds power to account.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.